Address given at Borrisokane Church on Sunday 17th March 2024, the Feast of St Patrick

Today we remember St Patrick, our patron saint,

whose feast day this is.

In the secular world, this

is a day for us to celebrate all that is right and true and beautiful in our

communities and in the homeland we share, whatever else may divide us. Many of

us I’m sure, wear a shamrock with pride, take part in or attend St Patrick’s

Day parades, and raise a glass to toast our nation. It’s allowed, you know,

even if you’ve pledged to abstain during Lent - the Prayer Book marks only

weekdays in Lent as days of discipline and self-denial. Some no doubt will

over-indulge and get up to all sorts of ‘shamroguery’, but we shouldn’t be

afraid to join in decent, patriotic celebration.

But as Christians, I

suggest we should go further. We should seek to find the real St Patrick behind

all the picturesque and fanciful legends that have grown up about him over the last

1500 years. And we should reflect

on what St Patrick’s life and mission has to say to us in Ireland today.

Much of what I was told about St Patrick as a child

is not true – it is much later legend.

Patrick did not

teach about the Trinity using the trefoil leaf of a shamrock, charming though

the story is. It first appears in writing in 1726, though it may be somewhat older.

Patrick did not

banish all the snakes from Ireland. That story is first mentioned by Gerald of

Wales in the 13th Century, although he didn’t believe it himself. The

truth is that Ireland was separated from Britain by rising sea levels after the

last ice age, which prevented snakes from reaching Ireland from Britain.

Patrick was not

the first to convert the pagan Irish to Christianity. The narrow seas between

Britain and Ireland, particularly between what is now northern Ireland and

southwest Scotland, were a trading highway in Roman times. Archeology shows

that many Irish settled on the west coasts of Britain, and no doubt British

Christians settled here. Irish chroniclers tell us that Pope Celestine

consecrated a Gaul named Palladius to be the first bishop for Irish Christians

in 431AD, a little before St Patrick. And there are traditions that there are

other Irish saints who preceded Patrick, including St Kieran of Seir Keiran, Co

Offaly, St Declan of Ardmore, Co Waterford and St Ailbe of Emly, Co Tipperary.

Most of what we know about the real St Patrick

comes from his own writings.

The main source is his

Confessio, or Confession, in which Patrick gives a short account of his life

and mission.

Patrick tells us, ‘My father was

Calpornius. He was a deacon; his father was Potitus, a priest, who lived at

Bannavem Taburniae.’ We do not

know exactly where Bannavem Taburniae was, but it may have been in Cumbria in

England, or Strathclyde in southwest Scotland, or in Wales. So Patrick came

from a Christian family of Romano-British clergy. His native language would

have been primitive Welsh, and no doubt he was educated in Latin.

He tells us he was

taken prisoner by an Irish raiding party, along with thousands of others, and

taken as a slave to Ireland, where he was put to work as a shepherd. Here his

love and awe of God grew, until after 6 years captivity a voice in a dream

urged him to run away and escape back to Britain, which he did.

After his return to

Britain, Patrick heard a call to ordination. There is a tradition that he studied

in Europe, in particular Auxerre in modern France, where he was ordained by St

Germanus.

In another dream,

Patrick heard the voices of the Irish among whom he had lived calling to him, ‘We appeal to

you, holy servant boy, to come and walk among us.’ Acting on this

vision he returned to Ireland as a missionary.

He was aware of the

work of other Christian missionaries in the south and east – Patrick was not

alone. But his focus seems to have been in the north and west, where the

Christian faith had not yet penetrated.

Patrick gives little

detail of his work, but tells us that he baptised thousands of people, ordained

priests to lead the new Christian communities, converted wealthy women, some of

whom became nuns, and converted the sons of kings. No doubt those he

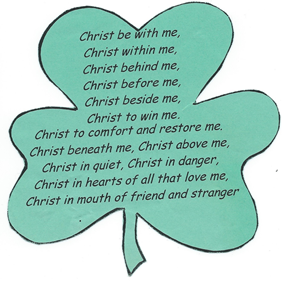

encountered were attracted by his distinctive spirituality, expressed in St

Patrick’s Breastplate, the famous hymn attributed to him. We shall pray a verse

of it, an invocation of Christ’ presence with us and around us, at the end of

the service.

His mission was not always

easy, for he tells us he met opposition. He was, beaten, robbed, put in chains

and held captive. But Patrick is undaunted. He rejoices in the results of his

mission, declaring that ‘the sons and daughters of the leaders of the Irish are

seen to be monks and virgins of Christ.’

Finally, Patrick was a

modest man. He finishes his Confessio with these words, addressed to us, to you

and me: ‘I

pray for those who believe in and have reverence for God. Some of them may

happen to inspect or come upon this writing which Patrick, a sinner without

learning, wrote in Ireland. May none of them ever say that whatever little I

did or made known to please God was done through ignorance. Instead, you can

judge and believe in all truth that it was a gift of God. This is my confession

before I die.’

What can we as Christians today take from the

life and mission of the real St Patrick?

1st, St

Patrick was passionately dedicated to sharing his Christian faith with the

pagan Irish. He saw it as a blessing, a gift from God. He echoes the words of

Tobit in today’s 1st reading (Tobit 13:1b-7): ‘Bless the Lord of righteousness, and exalt

the King of the ages. In the land of my exile I acknowledge him, and show his

power and majesty to a nation of sinners.’ We should be like him, eager

to share our faith in the public square in our own times, when so many find it

difficult to do so.

2nd, St Patrick knew

all about economic and social oppression from an early age. He challenged these

evils and faced persecution for it. To quote from St Paul’s words in today’s epistle

(2 Corinthians 4:1-12), he was ‘afflicted in every way, but not crushed; perplexed, but

not driven to despair; persecuted, but not forsaken; struck down, but not

destroyed’. When we in our times see oppression, or suffer it

ourselves, we should confront it as St Patrick did, and persevere against those

who seek to perpetuate it.

Lastly, in today’s

reading from John’s Gospel (John: 4:31-38), Jesus tells his disciples, ‘Look around you, and see how the fields are ripe for

harvesting. The reaper is already receiving wages and is gathering fruit for

eternal life, so that sower and reaper may rejoice together … I sent you to

reap that for which you did not labour. Others have laboured, and you have

entered into their labour.’ St Patrick reaped a harvest sown by

others, as he was not the only, nor the first Christian missionary to come to

Ireland. In later times the Irish Church found unity around his bishopric of

Armagh. In the same way, Christians of different traditions in Ireland today

should surely rejoice in the truly important things that we have in common,

rather than cling to the little things that separate us. Only then can we ‘gather

in the fruit for eternal life’ that Jesus desires us to reap.

I shall finish in prayer.

Hear us, most merciful God,

for that part of the Church

which through your servant Patrick you planted in our land;

that it may hold fast the faith entrusted to the saints

and in the end bear much fruit to eternal life:

through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen

;_Thomas_Becket_-_Luttrell_Psalter_(c.1325-1335),_f.51_-_BL_Add_MS_42130.jpg)